Devil in Disguise

Adopting Artificial Intelligence

In 1978, while I was in graduate school at Ole Miss, I was asked to propose a dissertation topic. I spent three months reading, talking with colleagues, and refining an idea I was excited about. When I finally presented it to my major professor, Mickey Smith, he read it carefully and handed it back a month later with a single sentence:

Find another topic.

I was disappointed. After another month of trying—and failing—to come up with something better, I went back and told him the truth: I still wanted to pursue the original idea. He paused for what felt like a long ten seconds, then said, “Okay.”

Perplexed, I asked why he had rejected it the first time.

Because it’s too ambitious, he said. You want to study the impact of computerization on the first pharmacists to install a pharmacy computer system. There are no pharmacy computer systems in Mississippi. Where are you going to find enough for a sample?

I’ll go to Atlanta, I replied.

He sighed. Okay. Good luck.

That moment, equal parts skepticism and reluctant permission, turned out to be my first real lesson in how technological change unfolds.

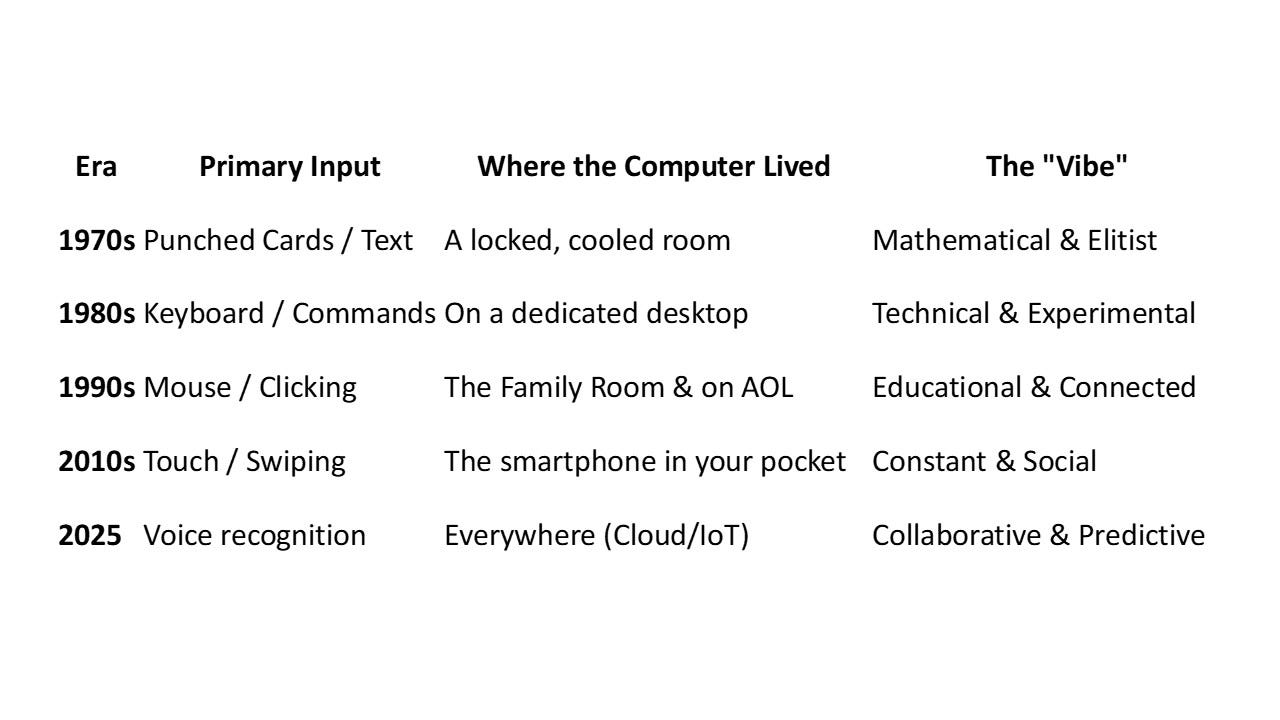

That was the situation in 1978. We were moving from the mainframe computer age to mid-sized computers, the size of a small refrigerator, and some intrepid pharmacists were beginning to realize the potential of this new technology and were early adopters. I have been a part of every computer generation since. I still remember the milestones that I personally experienced on the path to where we are today.

My first data was punched onto 80-column Hollerith cards one data point at a time and then run (repeatedly) through a card reader at the data center until I got it right. An 80-column Hollerith card was the physical medium that shaped early data processing and programming, and its legacy is still baked into modern computing culture. One unfortunate graduate student I knew was carrying a cardboard box full of Hollerith cards to the data center at night, tripped, and spilled all of them out on the ground. He almost quit the graduate program, and it extended his research by at least a month while he painstakingly re-punched all his data.

Summary of My Journey

Collaborative & Predictive

I installed local area networks, sent my first email over ARPANET, and joined the World Wide Web, first with a product called Mosaic, then Netscape, and finally, as it matured, Internet Explorer. Each step of the way, I learned from technical colleagues, and to this day, I still have a friendly relationship with techno nerds. That was a major accomplishment because the early users of the internet were very protective and viewed casual users as unworthy to have access to their network. This all crystallized around September 1993, when AOL gave its users Usenet access. Previously, each September brought a small influx of new college students who would learn the ropes from the experienced computer users. It was a closed society with rules-of-conduct about what you could and could not do. That stopped when large numbers of inexperienced computer users flooded onto the internet.

When the Internet Was a Small Village

Before the early 1990s, the internet felt like a small village with strong norms and sharp elbows. New users were expected to observe quietly, learn from more experienced participants, and avoid unnecessary disruption. People were not shy—but there were rules.

Two norms that today’s social media users might find instructive:

1. Flame wars were brutal—but principled.

Arguments were common and public, but:

You attacked ideas, not individuals.

Wit and technical accuracy mattered.

You were judged by how well you argued.

If you couldn’t defend your position, you were advised not to post it.

2. Status was earned, not claimed.

There were no follower counts, curated profiles, or influencers. Influence came from:

Answering hard questions

Writing good code

Posting insightful explanations

Being consistently right

Credentials mattered far less than competence.

All of that changed in September 1993, when AOL opened Usenet access to millions of new users overnight. What had been a slow apprenticeship model became a flood. Norms collapsed. Veterans grew resentful. Newcomers felt unwelcome.

You can trace a straight line through internet history:

AOL sucks → Read the manual → Google it → censorship debates → social media flame wars → trolling.

It was the first large-scale clash between insiders and everyone else—and the insiders lost. I was there to see it from the ranks of academia, and it was not pretty.

The AI Moment Feels Familiar

We are seeing a remarkably similar moment with artificial intelligence.

AI adoption among non-technical users has exploded over the past two years, largely because of accessible tools like ChatGPT©, Claude©, Gemini©, and others. Millions of people now use AI for writing, research, learning, and problem-solving without needing technical ability. But adoption stays uneven.

Some people enthusiastically integrate AI into their daily workflows. Others are curious but hesitant. And a meaningful minority are true non-adopters—not merely late adopters, but people who actively distrust the technology.

Many people I meet view AI through exactly this lens. They worry, often rightly, about privacy, manipulation, and the long-term effects on their children and society.

It reminds me of an Elvis Presley song, Devil in Disguise, released in 1963. The song’s memorable hook describes someone who appears angelic but is deceptive - You look like an angel, walk like an angel, talk like an angel, but I got wise, you’re the devil in disguise. There are many that I meet who harbor a deep distrust of artificial intelligence and view it suspiciously.

Here’s the paradox:

While some people reject AI entirely, nearly half of the U.S. workforce is already using AI at work without knowing whether it’s allowed, and a large portion knowingly uses it improperly.

The devil isn’t always the technology itself. Sometimes it’s the quiet, unexamined adoption.

The percentage of true non-adopters who both distrust AI and refuse to use it is likely 15-25% and declines as AI becomes embedded in everyday tools and services. In fact, most individuals who own and drive a late model vehicle probably don’t realize that the crash avoidance and lane departure functions are AI applications. They probably would have difficulty finding a garage that would even try to service their vehicle without AI-embedded diagnostics (e.g., onboard computer).

So, How Do You Respond to the Non-adopters?

People have legitimate concerns about privacy and the misuse of personal information. These concerns will not be easily overcome unless and until AI companies or government agencies adopt meaningful safeguards. That may take time. Waiting for government assurances is a faint hope; so far, there has been little sign that regulators are prepared to act decisively on AI.

In the absence of clear regulation, responsibility is likely to fall on technology companies themselves. A logical strategy would be for companies that design and market AI tools to implement strong privacy protections before they are mandated. History suggests this approach can succeed: Apple, for example, has gained a competitive advantage by treating privacy on its devices (e.g., iPhone, MacBook, etc.) as a selling point rather than a regulatory burden.

Recent events underscore the urgency of this responsibility. Following the death of a high school student who died by suicide after interacting with GPT-4, OpenAI has shown signs that it is taking the psychological and ethical dimensions of AI use more seriously. Whether such steps will be sufficient remains an open question, but they suggest that voluntary safeguards, if taken seriously, may arrive sooner than government mandates.

Provide transparency and control - Give users genuine control over their data with clear, understandable options. Allow them to opt out of having their shopping data and health records automatically included in a large database that is used to train AI agents. The non-adopters often aren’t anti-technology; they’re anti-opacity.

Demonstrate concrete value - Some holdouts will adopt when the benefits clearly outweigh their concerns. During COVID, many privacy-conscious people used contact tracing apps when the public health benefit was tangible.

The authors of a recent study on AI adoption noted the following in their conclusion:

As the role of AI within organizations and wider society continues to change, finding the right balance between harnessing its benefits and addressing potential risks is crucial.

Perhaps the easiest way for people to become comfortable with AI is the most obvious. Have them download several of the more popular AI chatbots and play with them. People discovered the value of the World Wide Web by using a browser (e.g., Google, Firefox, Internet Explorer). They quickly learned that they could change the heat element in their dryer using instructions downloaded from the WWW and avoid a costly service call. They learned the value of having quick and easy access to information. That is what AI chatbots do; they access information very, very quickly.

Getting Started

Artificial intelligence chatbots like ChatGPT are no longer just for technology experts—they are practical, everyday tools that can help people write, think, organize, and learn. These chatbots work as knowledgeable assistants, using advanced language technology to understand what you are asking and respond in helpful ways.

Unlike traditional software or search engines, chatbots are interactive. You make a request, receive a response in seconds, and can then ask for revisions or clarification. Whether you need an explanation, a draft email, a PowerPoint© slide, a Microsoft Word© document summary, or help exploring new ideas, you can simply describe what you want and the chatbot does the rest.

For beginners, the key is to think of a chatbot as a patient partner rather than a technical system. You stay in control, choosing what to use, change, or discard. I personally use different AI chatbots for different tasks, depending on what I’m trying to achieve.

Here’s a ranking of the most popular AI chatbots based on market share (2025) data.

ChatGPT (OpenAI): By far the most popular, with billions of monthly visits and a huge market share, leveraging its powerful models and ecosystem.

Google Gemini: Strong second, benefiting from Google’s integration and massive user base, with hundreds of millions of monthly visits.

Microsoft Copilot: Integrated into Microsoft products, it ranks high in market share and visits, often competing closely with Gemini.

Claude (Anthropic): Known for its long-context reasoning and high-quality answers, often preferred for complex tasks.

Perplexity: A leader in AI search, focused on providing cited, research-oriented answers, making it a top choice for information gathering.

Grok (xAI): Gaining traction through its deep integration with the X (formerly Twitter) platform. I find that Grok is better at finding photos and creating images.

DeepSeek: A strong performer, particularly in some regions, known for customization and performance.

Many of you already use one or more AI chatbots each day. If you’ve learned to integrate AI into your routine, you can probably skip ahead. For everyone else, the next section is designed to help you feel more comfortable and confident in learning how AI can help you.

The steps are simple and will feel familiar. They closely resemble how you learned to use other internet-based tools, such as email, social media, weather apps, or word processing.

Step 1 – Download several AI chatbots, but choose one to experiment with

Most of the chatbots have free tiers to entice people into using them. Begin with a single, well-known chatbot so you are not overwhelmed by options.

People often start with ChatGPT, Microsoft Copilot©, or Google’s Gemini© because they have simple web and mobile apps. You don’t need to compare tools yet. Pick one and get comfortable with it.

Go to the tool’s main website or install its official app.

Create a free account with your email; free tiers are usually enough for learning.

Pin it in your browser or on your phone’s home screen so it is easy to access.

Step 2 – learn how to phrase the question. In AI language, it is called a prompt. In general, I use the following format:

I’m [Role]: Who are you, or who should the AI pretend to be? (e.g., I am a teacher.)

I Want [Task]: What do you want done? (Summarize, draft an email, explain, create a plan)

I have [Constraints]: Background it should know (audience, goal, limitations, time).

Show me [Specific Format]: How the response should look (bullets, table, outline, word limit).

Challenge my assumptions.

Example prompt using this formula:

I am a manager writing to my team about a new project. You are a clear, concise communications coach. Draft an email announcing the project, include three bullet points on what’s changing, and keep it under 200 words.

Step 3: Start with three starter projects.

Pick small, repeatable uses so the chatbot becomes part of your routine.

Common starter projects:

Everyday writing: emails, social posts, meeting agendas.

Learning topics: ask it to explain concepts at different levels (child, college student, domain expert) or to quiz you.

Planning: draft to‑do lists, trip outlines, study plans, or meal plans, then adjust them together. Someone I follow on Facebook© had a chatbot plan for their vacation and was extremely pleased with the results.

Document triage: Paste a long article, report, or email and ask for a concise summary.

Brainstorming: Generate ideas for blog topics, sermon themes, class discussions, or presentations.

For each project, save 1–2 successful prompts in a note on our computer or smartphone so you can reuse and tweak them instead of starting from scratch every time. If you use the same chatbot, it will remember what you were researching during past interactions and will often weave those words or concepts into your new project.

Several widely used chatbots (Grammarly© and MS 360 Co-pilot©) are built into the software that you routinely use and are accessible while you compose a document, develop a spreadsheet, or create a slide.

Step 4: Practice safe and critical use

AI chatbots can sound confident even when they are wrong (e.g., hallucinations), so you need to verify their answers. I once had a chatbot document, a claim with a citation to a journal I didn’t recognize. I ran it through a second chatbot, and it confirmed my suspicions – the journal didn’t exist.

Double‑check important numbers, dates, and citations against sources, especially for work, health, or legal decisions. If I want confirmation, I run the same prompt through several AI chatbots and compare the results.

Avoid pasting highly sensitive personal, financial, or confidential work information into public AI chatbots. Confirm your organization’s AI policy and comply with any prohibitions on using confidential data in these systems. Many AI tools state in their terms that user inputs may be logged and used to improve the service or train models. Unless enterprise privacy settings or opt-outs are in place, you are taking a risk that your privacy and confidentiality will be compromised.

When something seems off, ask follow‑up questions like What is your source? Or show me this step by step. Provide citations to the literature. Ask the chatbot to narrow the focus and try again.

Skill comes from small experiments and knowing what to ask, not memorizing prompt tricks.

Step 5: Experiment and use iterative prompts.

If the first response isn’t quite what you needed, don’t give up. Ask follow-up questions or rephrase your request. You might say, Can you make that simpler?” or Can you give me more detail about the second point? Think of it as a conversation where you’re working with a colleague to find the answer you need.

This playful iteration helps build intuition quickly—what the AI is good at and where it still needs guidance. The goal isn’t perfection, it’s habit formation. When you notice a shift from, I need to Google that to I need to ask my chatbot, you’re on the right track. We already do this instinctively with voice assistants. Just say, Hey Siri or Hey Google, and they respond, waiting expectantly for you to collaborate with them to find an answer. Similarly, we use an AI-enabled interface on our smartphone when we drive a car and ask for directions or interact with smart home technology.

Recommended readings for beginners

If you want to go beyond tips and understand what is happening under the hood, these accessible resources help.

A Beginner’s Guide to ChatGPT: How to Get Started (CNET) – step‑by‑step walkthrough of setting up and using a chatbot for everyday tasks.

The Ultimate Guide to Writing Effective AI Prompts (Atlassian) – clear advice on persona, task, context, and format with concrete examples.

Co-intelligence: Living and Working with AI (Ethan Mollick) – A University of Pennsylvania professor who is an acknowledged expert on AI and authors a popular Substack Channel.

AI chatbots are computer programs that can hold written conversations with you, much like texting a very knowledgeable assistant. They use advanced language technology to read what you type, predict helpful responses, and adapt to the way you ask questions. Instead of clicking through menus or search results, you can simply describe what you need—an explanation, a draft email, a summary, or ideas—and the chatbot will generate a reply in seconds. For beginners, it helps to think of a chatbot not as a machine you must talk tech to, but as a patient partner that can brainstorm, explain, and rephrase things on demand, while you stay in control of what to accept, edit, or ignore. Pay attention to which types of questions get you the most helpful responses and which AI chatbot provides them. Over time, you’ll develop a sense of how to phrase prompts effectively.

Welcome to the New World

AI chatbots are powerful tools, but they’re not perfect. They can make mistakes, and their knowledge has limits. For critical decisions, especially about health, legal, or financial matters, always verify information with qualified professionals.

In short, AI is becoming an unbelievable technological tool that serves as a co-pilot and an idea generator. But the navigator, the one who ultimately says this path feels meaningful/ethical/promising, is still you. For some individuals, it will be a devil in disguise, and they will continue to harbor doubts about its purpose. For others, it is simply a tool, added to an extensive list of internet tools that they have evaluated, found useful, and adopted.

I am reminded of my father, an accomplished carpenter, who would often remark, You can measure the skill of a carpenter by the tools they use. A similar admonition appears in Paul’s letter to the Thessalonians: Test everything; hold fast to what is good (1 Thessalonians 5:21). Paul is not urging cynicism but discernment. Test everything assumes curiosity, openness, and engagement with the world as it is. Hold fast to what is good, supplies the moral anchor—not merely sampling ideas, practices, or teachings, but clinging to what proves life-giving, truthful, and faithful. Artificial intelligence is now part of our universe, and it is up to each of us to discern how, and whether, it becomes one of the tools we choose to use well.

Alan - another great article! I will never forget being in UR’s business school in 74 and being herded into the auditorium for our Dean to talk about computers. Unlike you, he didn’t have a clue. When I went on to VT to get my MBA, I learned a lot more but the industry was still in its infancy (76-77). BTW, I punched a lot of cards using the IBM system 32 to feed the monster mainframe.😀 And today I have dabbed in AI but wholeheartedly agree with the parallels you draw to the internet. As you also point out, it all boils down to responsible users. Thanks again for a great read!