The Impossible Dream

I sat facing the eleventh-grade guidance counselor across a large, imposing wooden desk. She peered down at the information on the sheet in front of her and looked up at me over her reading glasses. After a pause, she assessed my chances of success and, at the same time, challenged me. It’s obvious from your LSAT results that you need to be prepared to work with your hands. I was not surprised. I came from a middle-class family where putting bread on the table was the most important goal, and getting an education was much further down the list of priorities. Maslow would have been proud.

My father was a carpenter who was dismissed from the ninth grade for failure to follow the rules (He wanted to smoke at recess, and that was not allowed). My mother graduated valedictorian from her high school in rural north Georgia, but allowed the girl who finished second to get the meager scholarship that came with the recognition because she needed to get a job. My parents' expectation was that I would follow in their footsteps and get a job.

I had worked part-time jobs, mostly in construction, and was currently stocking shelves at the local grocery store. Still, the guidance counselor’s summary judgment, although probably accurate at that point in my life’s journey, was incomplete. Based on my test scores, she was assessing my chances for success. She couldn’t measure the drive and determination that would get me the respect and, most importantly, the satisfaction I was seeking from a life lived fully.

I graduated from high school with enough credits to earn a diploma, but with grades that were not sufficient to gain entrance into a four-year college. I settled for the local community college and took a couple of general studies courses while working part-time. I applied to enter a large commuter school in Atlanta and, after a year of less than enthusiastic effort, was notified by the registrar’s office that they felt that it would be in our mutual best interest if I didn’t return after my first year.

It was at the height of the Vietnam War, and to avoid being drafted, I joined the Navy. Four years of discipline and increased levels of responsibility both raised my expectations and gave me confidence that I could achieve them. I had studied for advancement examinations in the Navy, and that gave me knowledge and the opportunity to apply what I learned. It also helped me to conquer my fears of failure. The most significant factor in raising both my expectations and my confidence was, as they say today, I married well. Not for wealth or status, but for character. I finally found someone who believed in me and the dreams that we shared. It made everything else in my life seem possible.

I returned to college and made the Dean’s List, entered pharmacy school, completed a rigorous curriculum, and entered graduate school at the University of Mississippi (Ole Miss). I completed four years of graduate studies, graduating with both a Master's and PhD in Health Care Administration, and began my academic career. At that point, I had been in higher education for eleven years of my life. It was not easy, but we prevailed. We pieced together a patchwork of financial support, working far too many part-time jobs, using Veterans Administration benefits, and when those ran out, obtaining a fellowship. There were many times when I would leave the house with only a quarter in my pocket. It was there so that I could call someone who cared: a friend, a fellow graduate student, or my wife when the car I was driving quit. Life as a perpetual student was difficult, but we found ways to succeed, something my eleventh-grade guidance counselor failed to recognize.

Today, many middle-class high school students are faced with the same obstacles. How and where to obtain the education that would permit them to seize the first rung on the ladder of success. It is not easy, and, even with burdening themselves with a staggering debt, it is becoming increasingly unlikely that they will succeed. This Substack blog post is about the financial challenges middle-class students face, and the next will explore ways in which higher education needs to change if they are to have a chance for success. Once a beacon of upward mobility, college education now feels more like a luxury for many, with tuition costs skyrocketing far beyond the reach of the average family. For some, it is becoming the impossible dream.

Cost of Higher Education

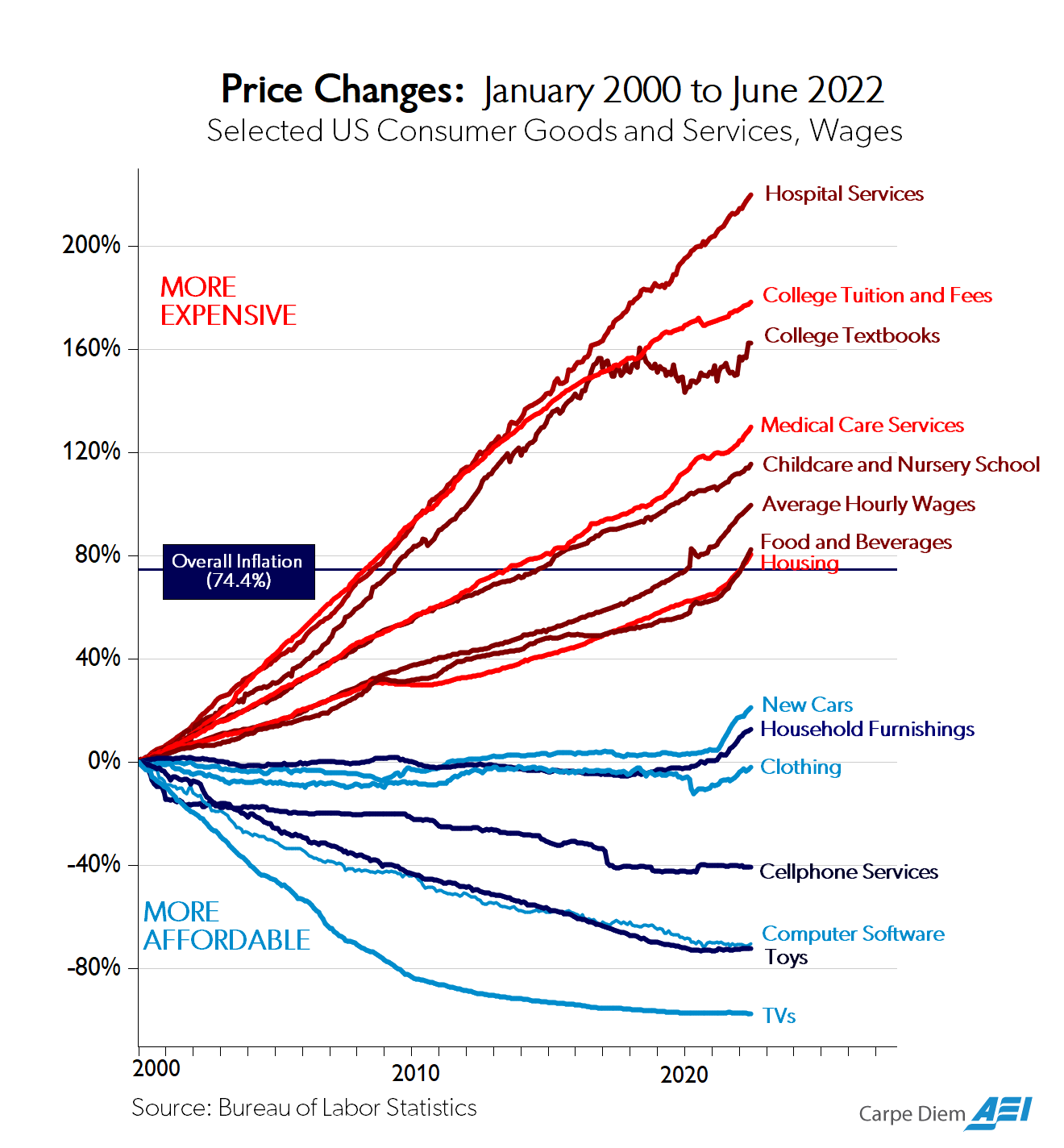

I recently came across a fascinating chart created by Mark Perry, a former Professor of Economics and Finance in the School of Management at the University of Michigan–Flint. It was referred to as the Chart of the Century in a Bloomberg article titled Chart of Century Gives Powell Gloomy Glimpse of Trade-War World.

Mark Perry's Chart of the Century is a highly influential and widely cited infographic that dramatically illustrates the divergent price trends of various consumer goods and services in the U.S. over the 21st century. It's a staple on his Carpe Diem blog and has been featured by major financial news outlets and think tanks.

The chart plots the percentage change in the Consumer Price Index (CPI) for a selection of goods and services, as well as the overall CPI and average hourly wages, from the base year of 2000.

The most striking feature of the chart is the massive increase in prices for services that tend to have heavy government involvement, regulation, or are less exposed to global competition. These are often depicted with red lines sharply rising. One of the largest increases was college tuition and fees. Perry and other economists conclude that government regulation at the state and federal level inhibits competition and, in many ways, reduces innovation. Government subsidies in the form of student loans and grants allow universities to raise prices for their goods and services with relative impunity. They are not incentivized to hold down costs, nor are there incentives for colleges and universities to change their business model.

Many are using the chart to predict the impact of tariffs on the price of consumer goods, the blue lines. I wish to concentrate on the red line, depicting the increase in the cost of college tuition and fees. Until the pandemic, the rate of increase had been steady and far in excess of the overall inflation figure. Obviously, the pandemic had a deleterious impact on enrollment and, by extension, revenue, even with government intervention. The rate of increase slackened, reflecting this once-in-a-lifetime event, but then resumed climbing and, unless affected by outside factors (more on this later), appears unlikely to abate on its own.

Theoretically, college is open to everyone, while in practice, it is often significantly more challenging for individuals from lower and middle-income backgrounds to access and afford. Here's a breakdown of why.

Rising Costs:

The sticker price of college (tuition, fees, room, and board) has increased dramatically over the past few decades, outpacing inflation and wage growth.

In 2024-2025, the average sticker price for a year of college was roughly $29,900 at in-state public universities and $63,000 at private universities.

Affordability Gaps:

Even with financial aid, many students, particularly those from lower and middle-income families, face affordability gaps – the difference between the total cost of attendance and what they can cover through grants, scholarships, and family contributions.

For the lowest-income households, the cost of attending a public four-year college can equal a very high percentage (sometimes over 100%) of their average annual household income, even after aid.

A report from the Institute for Higher Education Policy (IHEP) found that while students from the highest income brackets could afford 90% of colleges, low- and middle-income students could only afford 1-5%. Student loans, scholarships, and part-time work make up the difference.

Rising tuition, student debt concerns, and skepticism about the Return on Investment (ROI) of a bachelor’s degree are influencing decisions, especially among middle-class families.

A growing number of Gen Z students from middle-class backgrounds are electing to forgo four-year colleges in favor of trade schools, apprenticeships, vocational training, or certifications. Enrollment in vocational-focused community college programs was up 14–16% in Fall 2024.

Socioeconomic Gaps in College Entry

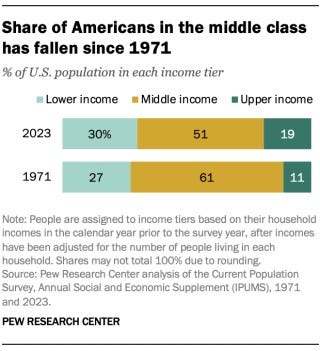

Defining the middle class can be tricky, as there isn't one universal definition used by organizations like the U.S. Census Bureau. Instead, researchers and organizations like the Pew Research Center often define it based on income relative to the national median, usually adjusted for household size. A common definition is households with an income between two-thirds and double the national median household income.

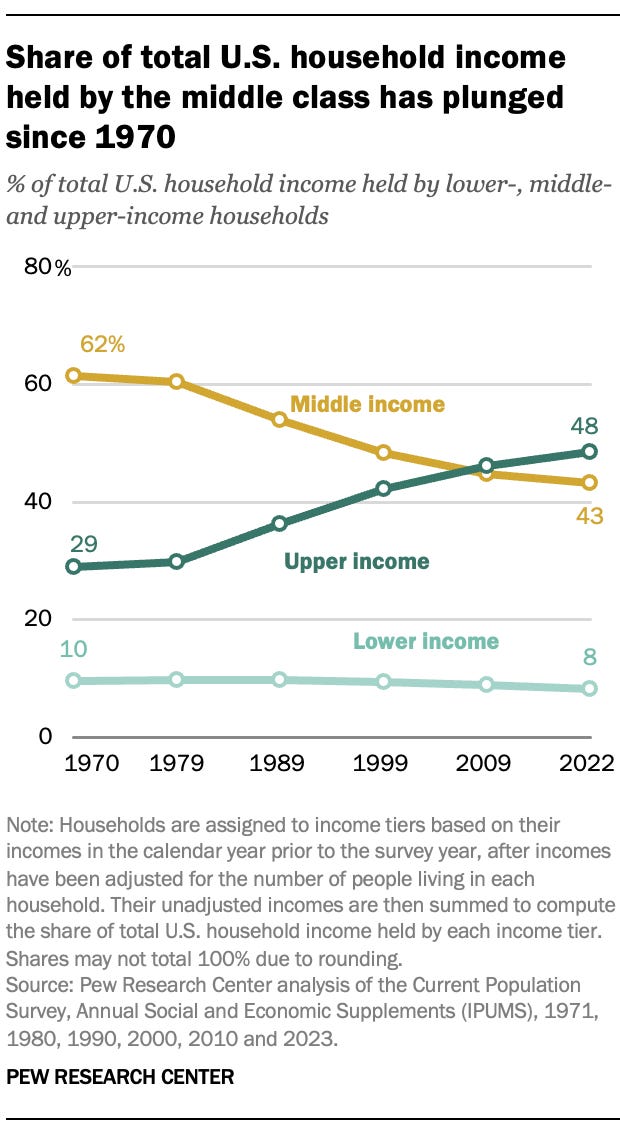

Based on Pew Research Center's analysis of government data (including Census data), the percentage of the U.S. adult population classified as middle class has been steadily declining over several decades. The growth in income for the middle class since 1970 has not kept pace with the growth in income for the upper-income tier. And the share of total U.S. household income held by the middle class has plunged. This has significance for higher education.

First, it is clear from this and other research studies that obtaining a college degree opens the door to social mobility. Among Americans ages 25 and older in 2022, 52% of those with a bachelor’s degree or higher level of education lived in middle-class households, and another 35% lived in upper-income households.

Second, individuals who move up into the upper income bracket occupy a high percentage of high-technology and finance positions. More than a third (36% to 39%) of workers in computer science and engineering, management, and business and finance occupations lived in upper-income households in 2022. About half or more were in the middle class. For most, higher education is a key to entering these high-paying occupations.

Social mobility typically follows after obtaining a college degree. The concern, however, is whether the parents of middle-income high school graduates can afford to send their children to colleges that could propel them from the middle to the upper class. Current projections by the Congressional Budget Office are that wages will increase by 1.5% over the next few years. The cost of living will increase even more, at 2 – 2.4%, meaning that middle-class families will fall further behind in meeting basic needs, and that would include saving for college educations. The Pew analysis noted that a significant pressure point for the middle class is the substantial increase in inflation-adjusted living expenses. Key areas where these rising costs are most acutely felt include housing, healthcare, and education. Going back to the Chart of the Century, higher education is outpacing the ability of its potential consumers to afford the price of admission.

The result has been a steady decline in the percentage of enrolled students from middle-income households. Based on data from the National Center for Educational Statistics and IPEDS, the number of students from middle-income households declined from 42% in 2000 to approximately 30% in 2024.

Year %

2000 42%

2010 39%

2015 36%

2020 33%

2024 30% (projected)

Middle-class representation among college students has declined steadily, largely due to rising tuition costs, stagnant wages, and increased reliance on financial aid among lower-income groups. The most affluent students have generally maintained or increased their enrollment share. At this rate, the prospect of obtaining a college education and a degree, affording them the opportunity of social mobility, may become an impossible dream.

The Impossible Dream

The original Broadway production of Man of La Mancha ran for 2,328 performances, from its opening on November 22, 1965, until its closing on June 26, 1971. It was very popular because it captured the optimism of individuals who aspired to conquer their fears and to achieve a lofty goal. Don Quixote, accompanied by Sancho Panza, sets out to right all wrongs and pursue his vision of a better world, famously battling windmills he believes are giants.

One of the most memorable scenes in the production was when Don Quixote attempted to explain to Dulcinea what he hoped to achieve during his quest. Don Quixote was hopelessly unrealistic, but he was committed to achieving his ambitious goal. The opening lyrics of the signature song began with:

To dream the impossible dream

To fight the unbeatable foe

To bear with unbearable sorrow

To run where the brave dare not go

To right the unrightable wrong

The Impossible Dream (The Quest)

from Man of La Mancha

Even though the imagery and storyline would not be familiar to recent high school graduates, the struggle is. To some graduates and their families, achieving a college education resembles tilting at windmills, not imaginary foes but realistic obstacles. Much of the disillusionment with higher education involves the perceived cost-to-benefit of an education and, unfortunately, often literally drops down to the bottom line. What do I get for my investment of time and treasure? There are no simple answers to a complex and highly personal question.

The high cost of obtaining a college degree is daunting but not impossible to overcome. Some of the solution resides with the parents and the graduates to make wise decisions about the best course of action in advancing their careers and achieving their dreams. It is the responsibility of leaders in higher education to take bold steps to reduce the cost of obtaining an education at their institution and to make their program as efficient and effective as possible.

The next Substack post will explore possible solutions from the perspective of a college leader and will examine successful innovations that, if adopted by an educational institution, could make the dream of obtaining an education more achievable.